The SEC has indicated that it is fast-tracking President Trump’s “suggestion” that quarterly reporting be eliminated. While it is unclear how the elimination of quarterly reporting will be implemented, one thing seems clear: unless the SEC increases the number of items that trigger an 8-K filing (or something close to that), there will likely be large gaps between filings. Phrased otherwise, there may be lengthy periods during which material nonpublic information will remain nonpublic. Since investors, like nature, abhor a vacuum, this strikes me as problematic.

We’ve been told that getting rid of quarterly reports is no big deal and that, among other things, the U.K. eliminated quarterly reporting a while ago and the world has not come to an end. That’s true, but it overlooks a critical distinction between the different approaches to disclosure that exist in the U.S. and the U.K. Specifically, public companies in the U.S. are not subject to a general affirmative duty to disclose material information; the opposite is the case across the pond. To clarify, U.S. companies are only required to disclose material information in limited circumstances, such as when there is a specific form requirement (for example, entering into a definitive material agreement, which needs to be disclosed under Item 1.01 of Form 8-K) or when the company or its insiders are trading in the company’s shares. And even when disclosure is mandated, the timing of disclosure is often left to the company’s discretion.

When I’ve advised companies of this approach, I’ve received many a puzzled stare from clients’ officers and board members. Some have even asked “well, why do we disclose all the stuff we disclose?” The answer to that question can be counterintuitive or downright confusing, but as a general matter that’s the law.

Thanks to my friend across the pond, Guy Jubb – a wise and good expert in corporate governance (and, incidentally, whose speech and diction are as impressive as or better than Richard Burton’s at his peak), I’ve been thinking about the U.K approach. Specifically, the U.K Market Abuse Regulation imposes a general duty on issuers whose financial instruments are admitted to a regulated market (e.g., the London Stock Exchange) to publicly disclose as soon as possible any inside information which directly concerns the issuer. Inside information is defined as information of a precise nature that has not been made public, directly relates to an issuer or financial instrument, and would likely have a significant effect on the price of the instrument if made public. Moreover, publication of price-sensitive information is required “without delay.” In other words, if you’ve got an important piece of price-sensitive information, you need to get it out there soonest, even if there is not a specific form requirement.

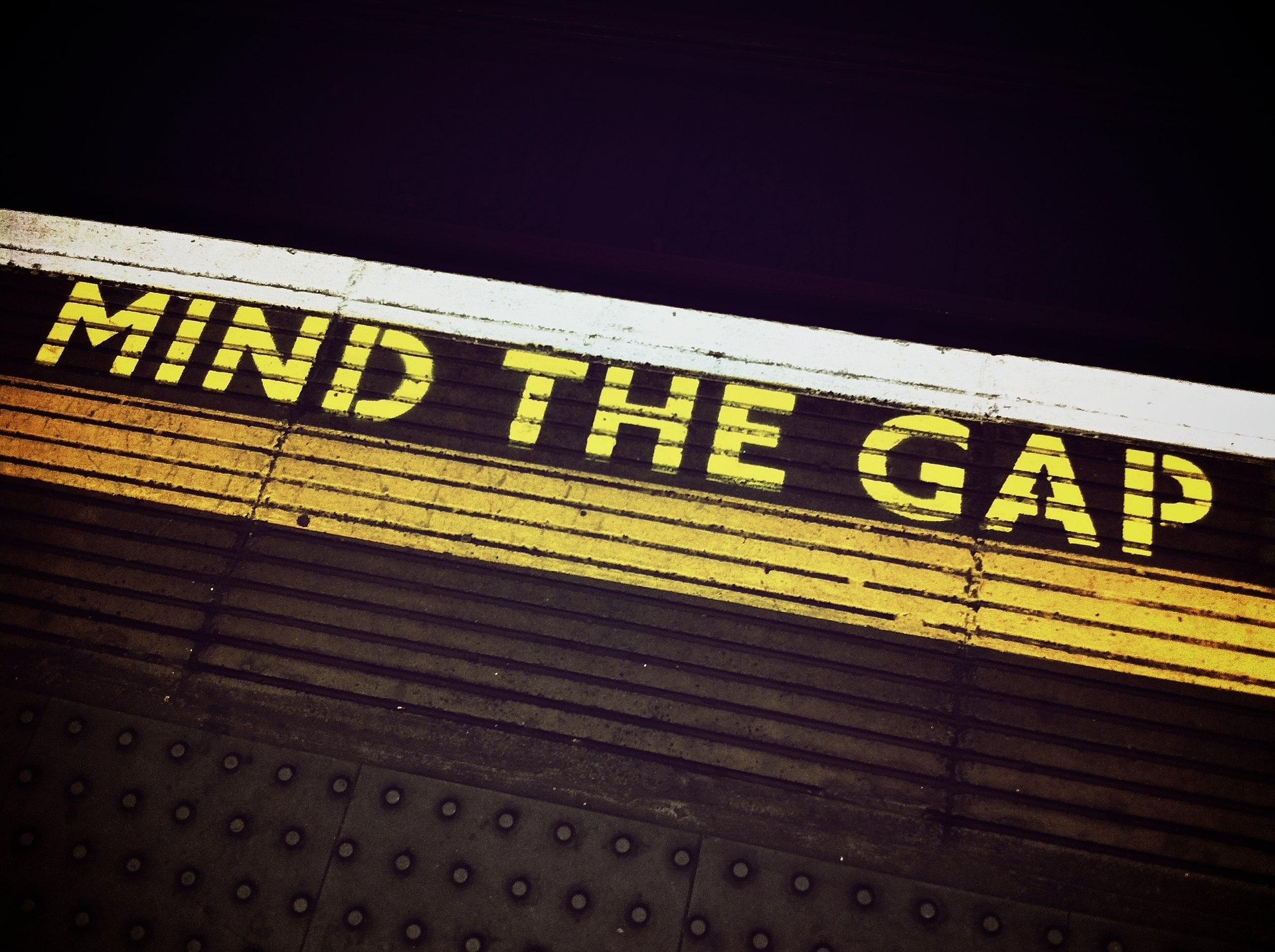

It seems to me that if there are to be long gaps between mandated disclosures, we need to switch to a process similar to that of the U.K. It may not be perfect, but otherwise we will have failed to “mind the gap,” to the detriment of investors, issuers, and quite possibly the capital markets themselves.